I’ve been looking at family portraits of the Cuban state. Five men dressed in matching light guayaberas and khaki pants pose smiling and affectionate in a group shot, two with their arms around an older man at the picture’s center: an old bearded man, wearing a track suit top. The men smile and look alertly at the camera. The old man does not smile but gazes at something beyond the camera’s address. An aging woman dressed in red stands on the right, looking down on them with a slightly quizzical look, as though unprepared for the photo.

The man at center is Fidel Castro and he has five sons. The woman is Dalia Soto del Valle, Fidel’s wife and the mother of his sons Antonio, Alejandro, Alexis, Alexander and Angel (yes, it sounds like One Hundred Years of Solitude). But these five men are not his sons.

The men are Gerardo Hernández, Antonio Guerrero, Ramón Labañino, Fernando González, and René González, otherwise known as Los cinco heroes, or the Cuban Five, who were reunited in Cuba as part of a prisoner exchange and diplomatic rapprochement with the United States. The photograph appeared in Granma, the official newspaper of Cuba on March 2, 2015, and the piece, with the byline, Fidel Castro, chronicles his reunion with these five “Anti-terrorist” heroes. The writing is full of patriotic vindication and a recapitulation of the role of the Five, which, the story notes “never hurt the United States.” The headline notes “Encuentro de Fidel con los Cinco (+ Fotos).” Of course, the photo supplement is the key to the lede.

The dutiful cheerfulness of these middle-aged men, the frailty of the old man at the center indicates an urgency to mark the moment: cheer up the patriarch and take a family shot while we’re all still in the picture. Out of the composition, somehow out of context from the smiling male camaraderie, Dalia Soto del Valle in her red dress haunts the scene, hinting at the uncanny nature of this family portrait, and its pathos too.

The men in their look-alike clothes seem like brothers or cousins color-coordinated by a photographer for a family shot, like many family photos taken in Miami, Hialeah, Orlando. These were taken by Estudio Revolución, a name that speaks volumes. That tendency of family portraiture, with a consistent uniform, has been a marker of tasteful bourgeois photos in many U.S. homes. And here they resurface, in the guayabera consistency of the heroes, who, like their linen shirts are formal and at ease: criollo sons back home with Fidel.

Beyond the first image, the candid shots show Fidel listening, being showed things, sitting in a circle of cordially attentive visitors, with his wife occasionally leaning in.

La casa de Fidel

The private world of Fidel, now open to viewing after decades of secrecy and privacy, is a site of great curiosity. Fidel’s face is known, while his private tastes and atmosphere has been until recently very closely guarded. The combination of political theater and private decor means we strain to read for meaning. In its ordinariness, the home is rather a shock. Fidel’s house is a house decorated by his wife Dalia, we imagine, a wife hidden too until recently, from public view.

The setting of many photos is a white tiled living room, filled with wicker chairs, art, a chandelier or two. Some walls are filled with paintings, kitsch mementos crowd coffee tables, stained glass catches the light. A grandfather clock is visible in an elegant dining room in the background. A large wooden statue of horses is a recognizable setpiece, usually visible behind the man once referred to as el caballo. Every object invites inspection, interpretation, critical choteo. A blog post from Miami circulated when the pictures emerged. It ridiculed Fidel’s dictator chic: this was both a misreading and somehow insulting to many Cubans or Latinos, whose homes resemble this one. The home around it reflects no particular chic at all but its opposite, a kind of improvisation, and seems to reflect custom, expediency and personal taste, and it is hard to identify signs of excess linked to the imagined decadence of dictators. It is marked with the social category and age of its inhabitants: gathering a lifetime’s gifts, no doubt, and accidental collections, the kind many people have to reckon with when aged parents move or pass away.

The tropical bourgeois decor, the wicker, the wood and porcelain, the hanging plants, the medicines on a table — all these details render the scene both familiar and uncanny as a set for political theater. The home is certainly luxurious by Cuban standards and far from the bareness of many Cuban homes, which lack basic resources like reliable wiring or plumbing, much less glass chandeliers. A cynical reading might imagine a Cuban Lifestyles of the Rich and Socialist, celebrating plenty and banality among the clase dirigente amid general scarcity. But the creature comforts do not seem disproportionate: they mirror the aspirational decor of many Cubans at home and in the diaspora. In strategic ways, the photos expose and confirm the “everydayness,” the “familiarity” of Fidel’s domestic life.

An airy room or terrace is set aside for cool repose. The circle of chairs, however, as its image multiplies in reports, is not exactly a living room, but a stage set for photo-ops, or a kind of political waiting room with Fidel. And while the former Maximum Leader’s “report” in Granma compares the Heroes’ experience to his youthful exploits at Moncada, the pictures tell a different story, one that is far from the official portrait of the “heroes” taken with Fidel’s brother Raúl.

Here the men, in their plaid shirts (famously a sign of state operatives among Cubans) stand side by side with their arms intertwined. Raúl stands at center but slightly ahead of them, as though he were leaning forward. They are in some public space, perhaps a state ministry, on the day of their arrival on December 17th, 2014. Many photos were taken and released of the arrival, also taken by Estudio Revolución. The body language seems stiff, and it seems as though either the “Heroes”or Raúl could be figures at a wax museum or added through CGI. The distance between the photographs speaks volumes about official iconography of Cuba in the last decade.

With the poignant portraits of Fidel at home, the Cuban state circulates images of a public retirement and of a decisive silencing. Selected visits by Cubans or heads of state (Kirchner or Maduro) reveal Fidel as a figure of domesticity, hospitality, gesture, and privacy. These are silent pictures. Without Fidel’s voice we want to know forensically about his body, its illnesses, the operations: we want the details of the political autopsy we are witnessing. Displacing the powerful voice and iconic virile revolutionary portraits of Fidel in black and white by artists like Korda, which often showed Fidel in mid-sentence, this new silent Fidel has taken hold: his thin and razor sharp profile, his age spots and grizzled beard, his wide eyed attentiveness or incomprehension. The photos of a political ghost in an eroded and becalmed body invoke pathos, resignation, and irrevocable mortality.

With these images of his face, far from the realm of “History Will Absolve Me” we “read” the words of a Fidel who confesses, in writing, “I was happy for hours yesterday.” This Fidel does not make history but listens wide-eyed, points, gestures, writes that he wants a family celebration.

Fui feliz durante horas ayer. Escuché relatos maravillosos de heroísmo del grupo presidido por Gerardo y secundado por todos, incluido el pintor y poeta, al que conocí mientras construía una de sus obras en el aeródromo de Santiago de Cuba. ¿Y las esposas? ¿Los hijos e hijas? ¿Las hermanas y madres? ¿No los va a recibir también a ellos? ¡Pues también hay que celebrar el regreso y la alegría con la familia.

Familial tenderness and enthusiasm, the cautious withdrawal and shielding silence, the epistolary and sentimental wisdom of the patriarch, become the very Cuban themes for Fidel’s laconic dotage.

Proofs of life and Commemorative Plates

Of course the photos, published in the official state newspaper, Granma, offer Cubans and the world a very thoughtfully conceived and sometimes urgently dispatched image repertoire for decline of the Revolutionary Leader and the revolutionary leadership. In the wake of the December 17, 2014 announcement, public speculation on Fidel’s health became more acute, and it became obvious that Fidel Castro had not been seen in public for a year. By January 9, speculation about a Cuban announcement of Fidel’s death made the rounds on social media, forcing retractions from news services and international newspapers. A proof of life seemed necessary.

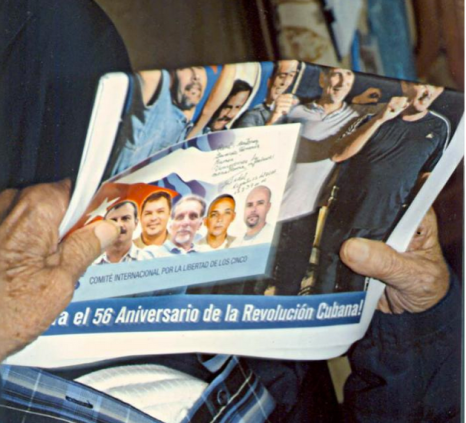

In early February, Granma produced photos of Fidel with the head of the Federation of University Students, celebrating the 70th Anniversary of his entry into the University of Havana. Randy Perdomo came to visit Fidel at home, and Granma published under his byline a report and photos chronicling his visit to Fidel. In Fidel es un fuera de serie (A youthfullly colloquial “Fidel is off the charts”), Perdomo recounts his visit, complete with a cache of his own photos. There are shots of Randy sharing pictures of the public celebrations for the returned heroes (a date and time stamp for the photo, proof of life), of Fidel’s hands holding a Cinco Heroes leaflet (more on that below), photos of Randy giving Fidel a commemorative plate, another tchotchke for the house.

Randy Perdomo’s visit underlines themes of time and distance: seventy years since Fidel’s entry into university, his status as a learner, his lay identity, his continuity with youth and youthful memory. The photographs, prosaically, will remind anyone of a grandson visiting with souvenirs or explaining current events to an out of touch grandparent. In one, Randy and Fidel watch the television, with Randy pointing out something of note. The photograph betrays a homey detail: the clock under the screen, easily legible to someone who wants to know when programs are on, or when they are over. Clocks for senior moments, markers of a pragmatic yielding to frailty, anxiety, inattention. Like Randy and his mementos, the intention seemed to render Fidel more familiar, and less and less uncanny.

The photographs of this most iconic and most photographed retiree remind us of several things. The familiarity of Fidel’s image in this new scene offers a banal and cultish value, echoing Benjamin’s reminder that “the cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead, offers a last refuge for the cult value of the picture.” Benjamin, like Freud, also reflected on the role of the uncanny, its oscillation between the strange and the familiar. Fidel has now to be compared with millions of other old men watching television, listening, sitting still. No longer being Fidel. The transformation of Fidel from public settings and olive drab to track suits have signaled not only his frail health but his retirement, his relegation from Maximum Leader to the diminished but powerful role of the ancient patriarch, homebound and hospitable, frail and in need of care.

As Raul inaugurated a regime of the brother, Fidel went from patriarch to abuelito, offering an uncanny supplement that erodes and displaces the old image archive archive of his authority. We are seeing images of the retirement of a mode of power. The public pictures of Fidel conform to those venerable readings of the King’s Two Bodies: Fidel as a body of authority and sovereignty in a political theology, and Fidel as a real living being, one who was dying but could not die, one who recovered, and must linger. Even in extreme ill health or sitting quietly at home, Fidel’s image still has power and value for the state. The uses of these images in official communication might lie, most cynically, in relegating Fidel’s waning life to a world of tchotchkes, sculptures, souvenirs. Open House, with Fidel as part of the taxidermy of the revolution’s bourgeois sitting room.

But perhaps most significantly, these recent photographs are offered as a forensic element: proof, complete with markers of date and time, that a sequestered body is still alive. Proof too, that the Cuban state wishes to circulate Fidel’s erosion not only as a protective icon, but as a sign of a decayed potency: a vulnerable but public sign of change and political mortality. The photographs are proofs of life for the state too, as it bides its time.

En manos de Fidel

The portrait of Fidel’s hands during the visit of the student offer a poignant version of that date and time stamp. They are images I find challenging:

The photograph of Fidel’s hands clutching a pamphlet celebrating the release of the Heroes, part of Randy Perdomo’s visit, seemed a curious image. They are proofs of life in real time, certainly, since they show him holding a recent publication. Fidel did not hold an announcement of the Obama changes, but pictures of his own, returned home. These two strange establishing shots mark Fidel’s seclusion from public life: they announce the arrival of the Five, whom Fidel had not yet met on their return. All of Cuba has seen them, the photos signal, but Fidel has not yet had the chance. He is no longer the first to know.

They are curious and apparently candid compositions, these photos of Fidel’s hands. Uncropped, and detached from his familiar face, these free floating hands give an impression of casual vulnerability. In one shot Fidel’s shirt is unbuttoned and shows a camiseta, taking us closer to his body and its mysterious afflictions.

The hands are old, gnarled by arthritis, marked by sunspots and deep wrinkles. The nails are clean and carefully groomed.One wonders if the hands are steady or if they tremble. The face is absent.

Fidel holds in his hands the news of heroes returned and the symbolic resonances multiply: the righteous end of his legacy, the vindication of his plans. More than that, with only hands visible in these photos, and Fidel outside the composition, the viewer is physically and figuratively in the place of Fidel, looking over him, looking from above at aging hands before him. The hands of power that manipulated order now being led, directed, manipulated themselves? The questions remain: is there a political reflection guiding the hands and not just their image? Is there reflection in Fidel at all? Must we think like Fidel, think for Fidel, who may well be lost in the dementia of many of his contemporaries? Most striking is the need for the representation: Why are these images of Fidel, in varied states of illness and dotage, still so useful, or so fetishized? Fidel has passed from public cult to private spectacle. The details of his mortal decay are as useful as his legendary resilience.

Those ancient hands invoke the hands of fathers and mothers, grandfathers and grandmothers. With photographs like these, against the grain of his monumental status as hero and villain, Fidel Castro begins to occupy a private imaginary for many Cubans. Grandmothers holding religious estampitas, grandfathers holding sportspages, grandparents holding graduation announcements or news of current events. They summon reluctant moments of identification.

For me, they evoke my father’s age, my father’s hands, his physical and mental frailty, his silence and laconic gestures. The photos of the living room, the medicines, the special chair for Fidel, evoke my parents’ home and the accommodations made to age and infirmity. It is an uncanny intimacy, an uneasy empathy. But it’s there, the display of decay, the mortality of a “historical” gerontocracy that has held three subsequent generations captive to a political primal scene.

For all our critical malice, in this image repertoire, Fidel cannot be understood only as a posthumous being. He is neither the zombie of Juan de los muertos, nor the decrepitude of Guamá’s acid parodies. He is a much more stubborn revenant, precisely because he mobilizes something more than horror or disgust, something cloaked in a troubling intimacy: the cult of care.

The exposed images of this vulnerability, the details of pathos and age are shocking and poignant. The image repertoire of Fidel’s privacy and his decline is very powerful. The photos invite identification and recognition, they whisper all the excuses of mortality and age. Making of Fidel an ancient everyman in need of care mobilizes secret piecemeal empathies, where modes of care and caring (for good or bad fathers, good or bad leaders) build up into an unconscious salve, a practical derogation of political judgment. The proof of vulnerability vanquishes the old fantasies of political killing, literal or figurative.

As psy-ops, it’s a brilliant move, cloaked in a thousand codes of national knowing, dispensations for viejitos, repertoires of tenderness for the old folks at home. In the public and private exhibitions of family portraits with Fidel, a million uncomfortable recognitions take hold, a threshold of resignation and relinquishment opens. The psychoanalytic possibilities multiply and leave open the questions. What will the new modes of authority be, in whose service is this uncanny pathos being deployed? When Fidel’s hands seem like your father’s hands: what is the political meaning of such an image? How does one care for an uncanny exhaustion?