On Mourning and Fidel

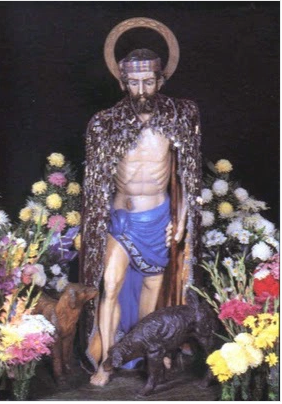

Fidel Castro’s ashes will be buried today, the 4th of December, 2016, in Santiago de Cuba. It is the feast-day of Santa Barbara, the Feast Day of Changó, and 49 years exactly since I left Cuba as a young child with my parents in 1967. The date has always been a secret anniversary for me, and the coincidence today speaks volumes about departures, mortality, and the end of an era. The towering figure of my childhood and youth, the man who has shaped the lives of millions of Cubans around the world, will be laid to rest today. He will be buried seven months after the death of my father, at a time when my father’s loss seems more raw to me than when he died. Fidel’s passing, like my father’s, seems ordinary, momentous, and mysteriously difficult to measure.

I am not saying that Fidel is like a father to me. But his descent into old age, his reclusion, his frailty, paralleled my father’s decline. I came to reimagine him in those years, and in the silence when I could no longer speak to my father about him, when my father could no longer speak to me about Fidel. Fidel’s legend, his image, his words and power were so enormously decisive in shaping my destiny that his death opens a time of remembering and reckoning. It makes me wonder what my father would say, what it would mean to him. And it makes me rethink my loyalties, my weaknesses, and the lifetimes we have all spent in his shadow.

Fidel Castro’s death marks for me the end of epic dimensions for Cuban history, the end of an agonistic history for Cuba and its diaspora. His passing marks once again how he came to stand for all of us in the eyes of the world.

“So what do you think of Fidel?”

Every Cuban I know has had to answer for herself or himself in trying to answer that wrong question correctly.

In the eyes of Americans, in conversations that demanded solidarities or condemnations, he came to be a kind of test, an unavoidable mirror through which others judged us, judged our politics and our sense of nation, even our common sense. He was invoked to test American anticipations of what a Cuban should think, to confirm prejudices about Cuba, about Miami, about Latin Americans, about exiles or refugees. To test our loyalty to the United States.

To disavow and hate Fidel was the religion of Miami, a city of counter-revolution, political bombings, and forced silences when I was young. When I left, that disavowal continued to seem like a passport demanded in many circles, something that would confirm my authenticity as Cuban. On the other hand, to express sympathy for Fidel’s ideals or achievements was a kind of soft salve in other spheres: it might impress my cosmopolitan hosts, bolster my left credentials, or prove that I was not some typical bourgeois reactionary.

Fidel was always the first or second question that anyone asked me when they learned I was from Cuba, that I had grown up in Miami. For decades, I felt myself float out of my body as I answered. To speak judiciously of his leadership, with measure and gravity, to speak of contexts and contingencies, to refuse to tolerate nonsense in Fidel conversations continued to be nearly impossible for me until very recently. In the end I always felt pushed to confirm the prejudices and judgments of my interlocutors, coerced to support their expertise on Cuba, Cubans, and their dramatic exile surplus.

To speak of Fidel in the United States meant sacrificing history and nuance, and it also meant leaving myself at the margins. It became such a routine demand, talking about Fidel, that little by little, it meant distorting myself into a fake oracle, an ethnographic case-study of what Cuban exiles should be. It was a banal but dangerous exposure.

It rarely revealed anything but a kind of forced performance, and left me filled with a mixture of pride and shame. Pride that Cuba was important, was important because of him. Pride that I was called out to weigh in on the political drama. Pride that he had refused an ordinary destiny for a Caribbean island in the twentieth century. Pride and shame both, since, without him and the Revolution, whatever its destiny, I would have been, in the eyes of my interlocutors, an ordinary and indistinct tropical Latina trying to sound like an intellectual. Shame that my performance was required, that my judgments were conscripted, shame at my real distance from what Fidel meant or did in Cuba. Shame at knowing that he was a foreclosed subject, that I was tired of hearing about him, that he was my parents’ story and not mine. Shame that I knew that I stood, arbitrarily, in the place of millions of people who might tell a different story. Shame at the profound loneliness of having to become a subject by judging Fidel.

Finally, in my thirties and forties, with fellow Caribbeans and Cuban Americans, with student friends from around the old third world in New York, it became possible to plumb the weight and contradictions of Fidel and his legacies. To understand him not only as the stronghold of the Revolution and its global reach, but as an inestimable psychic force. To laugh and grieve intimately at our indenture to our parents’ legends of Fidel, to confess analyses, sympathies, symptoms, and neuroses of Cuban memory and loss. With my sister and my best friend, with my lost friend José Muñoz and a with a group of Cuban American and Puerto Rican artists, writers, thinkers—some of whom, like me, were exiles from Miami— I could think about Fidel and the Revolution in new terms.

With my generation, with my friends, I didn’t have to choose, I didn’t have to denounce, defend, or perform. We shared a deep and hidden background, a counter-life to the myth of exceptional Cuban-American exiles. We shared a sense of politics. And we began to tell the truth for one another, including the sense of relief or frustration, the nagging existential doubt, at not ever having faced the choices our parents faced. We began to talk about the cost of the Cuban-American miracle in Miami or New Jersey. They’re not easy conversations: they’re complex and private and grave. They reveal intimate wounds and alliances, they are difficult and funny. They are for us.

The passing of Fidel has been heavy and uncanny, difficult to assimilate. Many of us, and most of our parents, Fidel’s contemporaries who chose to leave Cuba, have been repulsed by the public celebrations of his death in Miami last weekend. It was a new source of shame for me, this pachanga counter-revolution, a kind of lame regicide turned inside out as carnival with a selfie-stick. It felt demeaning, embarrassing, painful to watch. The youth of many of the participants made it seem like the celebration was over the death of history, that the memory of the last half century was being killed off in the street parade. In the context of U.S. politics and racist populism, it felt both bizarre and ominous. For those that remember, or want to remember, marking Fidel’s death instead demands real gravitas: in both Cuba and its exiles the ambitions were great, the costs were heavy.

Like me, Cuban Americans of a certain age have been infected with that gravitas, afflicted lately with a sense of disorientation and loss. We might be reflecting today on what it means to mourn, and what we love and hate about Cuba and ourselves. We mourn bonds broken. We mourn losses of love and time, broken links of friendship and kin. We mourn our parents’ secrets and sadness, their dispossession and resolve. We mourn their disappointments. We mourn the lies that we grew up with. We mourn the violence we were close to. We mourn the ordinariness of a native land. We mourn the Cubans we never met, the other selves we might have been. We mourn our disillusionment with political love.

Today, Cubans on the island who lived with Fidel as their Comandante are due the respect and privilege of mourning their leader, of speaking about him, of judging his legacy. Today, the exiled Cubans of his generation, who shared the joyful beginnings of Fidel’s Revolution, are due their moment to remember the days when their choices still hung in the air, uncertain.

Those of us who grew up in the United States as the children of exile, marked by Fidel, have had to reckon suddenly and finally with his absence: the ordinary disappearance of this embodiment of fate, the end of our Cuban predestination. Some of us feel the weight of his passing in the same way we felt his life: with an urgent and uncanny attention, a compulsion that joined us to Cuba and kept us away. And, now, too a sense of both emptiness and awe.

As time passes and we honor our relationships to the people we love in Cuba, as we understand the Cuban everyday, and perhaps strain to know the everyday life that made the Revolution fifty and sixty years ago, we can relinquish our forced positions and our performances, and try to learn something new. We don’t have to choose between celebration or grief. We don’t have to speak or pronounce judgment: we can refuse the choices laid before us. We can be still, and listen, and mourn for awhile. Until someone asks us that other wrong question: “So what happens next?”

We are in a state of shock and disbelief; relieved and disoriented, getting to the end of the roller-coaster ride and wondering how to live without the thrill or the safety restraint, how to step out of the car and back onto prosaic solid ground after the ride. People are asking us how it felt. We say things and are watching things go on but really we are still in Havana on Monday and Tuesday. We are still reckoning with the press conference. We are still parsing the speech. We are still in the audience. And despite all our jadedness, our pessimisms of the intellect and optimisms of the will, despite all we can muster of cynical reason and disillusion about Cuba and Obama’s trip, we are many of us in a secret and sober state of joy. A kind of after-glow.

We are in a state of shock and disbelief; relieved and disoriented, getting to the end of the roller-coaster ride and wondering how to live without the thrill or the safety restraint, how to step out of the car and back onto prosaic solid ground after the ride. People are asking us how it felt. We say things and are watching things go on but really we are still in Havana on Monday and Tuesday. We are still reckoning with the press conference. We are still parsing the speech. We are still in the audience. And despite all our jadedness, our pessimisms of the intellect and optimisms of the will, despite all we can muster of cynical reason and disillusion about Cuba and Obama’s trip, we are many of us in a secret and sober state of joy. A kind of after-glow.